The Origins of Black History Month

As a Harvard-trained historian, Carter G. Woodson, like W. E. B. Du Bois before him, believed that truth could not be denied and that reason would prevail over prejudice. According to an article in the Library of Congress written by Howard University history professor Daryl Scott, Woodson’s hopes to raise awareness of African American’s contributions to civilization was realized when he and the organization he founded, the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH), conceived and announced Negro History Week in 1925. The event was first celebrated during a week in February 1926 that encompassed the birthdays of both Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.

The celebration was expanded to a month in 1976, the nation’s bicentennial. President Gerald R. Ford urged Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.” That year, 50 years after the first celebration, the association held the first Black History Month.

Each week during Black History Month, The Examiner highlights and honors a black person of importance to the community of Southeast Texas. From business owners and administrators to doctors, lawyers and government officials, Southeast Texas is brimming with black leaders and role models.

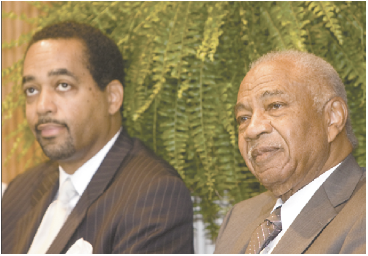

This week, The Examiner is honoring two local “giants” in an effort to perpetuate their legacies as Civil Rights-era attorneys. In a time when black people faced overwhelming prejudice in every aspect of their lives, the work of Johns and Willard led to reason prevailing over prejudice in Southeast Texas.

Commemorating “Crusading Lawyers” Johns and Willard

Immortalized in bronze as two welcoming faces at the entrance of the Jefferson County Courthouse, where they opened doors for fellow black people into previously white-only establishments, sit the duo of Judge Theodore R. Johns Sr. and Elmo R. Willard III.

Both men served as lawyers during a time when black people – in the eyes of the law and some sects of the populace – were considered second-class citizens to their white counterparts. In fact, reports reveal the men were not allowed to approach the judge’s bench and had to represent their clients while physically standing behind white lawyers.

More than 300 attorneys, government officials, business leaders and all manner of thankful Southeast Texans paid tribute to Johns and Willard at a ceremony unveiling bronze busts of the “Crusading Lawyers” held in 2008 at the Jefferson County Courthouse. Among those thankful Southeast Texans were three attorneys, Wayne A. Reaud, Gilbert I. “Buddy” Low and Michael Jamail, who commissioned the bronze busts.

When questioned at the bust unveiling ceremony if he ever thought he would see the day when his efforts were honored in such a manner, Johns remarked, “I never thought of this, not in my wildest dreams.

“Things were different back then. Can you imagine? Back then we had black police officers that couldn’t arrest white people if they were committing a crime, and we had segregated restrooms at the courthouse. We had jurors that were identified with the letter “C” colored by their names.

“This means so much to me. It means the community and Beaumont has changed. I would just call this the greatest thing, and any problems that we have now, we can solve those if we work together.”

Speaking on behalf of his late father, David Willard told those in attendance of his memories of his father and how, looking back now, he knows his father was a giant of a man.

“In my eyes, as a small child, he was a giant,” David Willard said at the unveiling. “I think I always knew that my father was highly regarded by those I encountered. My only regret is that he is not here today to see the love that this community is showing for the work he did and for the community that he loved so much.”

Sons of Southeast Texas

Beaumonter Elmo Willard III and Silsbee native Judge Theodore Johns were born in 1930 and 1927, respectively, in Southeast Texas. These men were born to a time of economic despair, with their births straddling the 1929 stock market crash that would precipitate the Great Depression.

Both men attended Historically Black Colleges and Universities, with Johns staying close to home at Prairie View A&M and Willard traveling to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Their early educational experiences would prepare them to take the next step that would transform not only their lives, but those of their countrymen.

Some years apart, each enrolled in the Howard University School of Law in Washington, D.C. and met Charles Hamilton Houston. This remarkable man – then-dean of the school of law – was responsible, perhaps, more than any single person, for laying the legal foundation for what would become the Civil Rights Movement. With his pupil-turned-protégé Thurgood Marshall, Houston set out to overturn the 1896 Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, which had established the “separate but equal” provision validating repressive Jim Crow laws that smothered the embers of progress for African Americans for decades.

Under Dean Houston’s tutelage, a cadre of civil-rights-minded attorneys sprouted. Those young black men would go forward as fledgling lawyers and challenge these laws in multiple venues across the nation.

After graduating from law school, Johns was preparing to start his own practice when he received a draft notice to serve in the Korean War as a Marine. A real-life embodiment of the mythological figure Odysseus, Johns returned home after war and rid his home of wickedness in the courtroom.

In a 1998 oral history preserved in the Tyrrell Historical Library, Johns said, “I was over at Joe Guidry’s barber shop here in Beaumont getting a haircut. I really hadn’t planned to practice here, but they were telling me about a case – property case – and they said they didn’t believe I could handle it … and I said, ‘Well, I’ll take it.’ And I took the case; and I went to court; and the judge ruled in my favor.”

From that barbershop beginning, Johns began practicing law in Beaumont 69 years ago in 1953. As fate would have it, he met Willard the following year as the recent Howard graduate was preparing to take the bar exam.

Johns said they discussed forming a partnership, and, after Willard passed the bar, they did. For more than three decades, the two men practiced law together in Beaumont. But, with no more than five years of combined experience as attorneys, the duo altered the course of Southeast Texas history by earning black students the legal right to attend what was then Lamar State College of Technology, now known as Lamar University.

Crossing barriers as crosses burn

The landmark lawsuit Jackson v. McDonald, which enabled the first African-American student to enroll at Lamar State College of Technology in 1956, was perhaps the most notable and impactful case Johns and Willard litigated.

One response to the courtroom crusading conducted by Johns and Willard was violence in the streets of Beaumont, but the events they set in motion altered the social fabric of the college and city. A tumultuous time that began with the Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 would culminate with the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but the Lamar lawsuit – won by Johns and Willard – brought this confrontation to Beaumont that was still being defined nationally.

“Some states didn’t address that problem as early as we did here in Southeast Texas,” then-Lamar President Jimmy Simmons told The Examiner in 2008. “The result of that hurdle in 1956 paved the way for Lamar University to become one of the most diverse campuses in the country.”

The lack of educational opportunities in Southeast Texas for black people was especially acute considering their exclusion from campuses like Lamar State College – an institution the Lamar Board of Regents said was created for “whites only.”

After the institution corrected a so-called mistake that led to a black student earning admission to Lamar in 1952, seven black recent high school graduates applied for admission in 1955. Most of the students had completed at least one successful year of college elsewhere before applying. Their application would not be quietly swept under the rug like that of James Briscoe three years prior.

After Lamar regents announced a meeting to consider the situation, a group of white people delivered a letter of protest. While each protest carried words of prejudice, some included violence and attempts to intimidate black students from seeking an education alongside their white peers.

In a display of sheer hatred, integration protests placed a 15-foot-tall burning cross across from the main entrance to campus as one of several such acts of terror. Seemingly siding with the cross-burning crowd, the Lamar Board of Regents voted to deny admission to all seven students, declaring the legislature created the school for “whites only” – and besides, they added, “an unprecedented growth in student population” meant Lamar could not take on any more students, though they did promise to reconsider their pro-segregation stance at a later date.

Unwilling to wait for the board to come to the just conclusion, Johns and Willard filed a lawsuit styled Jackson v. McDonald. The case went to Judge Lamar Cecil, who had been appointed by President Dwight Eisenhower in 1954. Attorney General John Ben Shepperd offered a variety of arguments on why the lawsuit should be dismissed, but Cecil was unconvinced. In fact, the 1954 Supreme Court decision gave him clear precedent on the matter.

On July 30, 1956, he ruled that qualified black students had a right to be admitted to Lamar, reiterating that the doctrine of “separate but equal” was no longer the law of the land. Two days later, another cross burned at Lamar. The following week, two more were torched. Among the protest leaders was a runoff mayoral candidate that year named Frances Lightfoot. Some described the white protests of Lamar’s integration as “politically unsophisticated” and lacking organization and leadership.

On the first day of integrated classes, protestors erected picket lines in front of most of the 11 gates at Lamar. Reports at the time say protestors were hostile and abusive toward many of the white students and faculty they were attempting to “save.” Police stood by and watched as picketers removed some black students from classrooms and stopped cars looking for others.

An insatiable sense of justice

After opening the doors for black students to attend Lamar State College, attorneys Johns and Willard said, “Not enough,” and began combating regressive, racist laws. They sued to open Tyrrell Park to people of all races, then moved on to libraries and other public amenities.

At the dedication ceremony, then-Senator Rodney Ellis praised both men before speaking about Willard.

“One of them had the opportunity to be a federal judge,” he recalled. “Now some say he didn’t get the opportunity to be a federal judge because maybe the timing wasn’t right. I suggest he didn’t get to be a federal judge because he made some powerful people angry.”

In fact, Congressman Jack Brooks and State Senator Carl Parker recommended Willard for appointment to the federal bench in letters to Sen. Lloyd Bentson.

Willard died in 1991 after a long battle with cancer. He was 60. Johns died at the age of 82 in 2010, two years after attending the unveiling of bronze busts honoring the “crusading” duo.

At the dedication ceremony, Ellis paid tribute to Johns and Willard as “two unsung heroes.” Recalling the Lamar case and the ensuing violence, he said, “We honor Judge Theodore R. Johns, who is here today, and we say, ‘thank you, sir.’ And we honor Elmo R. Willard. Judge Johns, I know there are many doors I walk through because you opened those doors.”