The function of education is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. Intelligence plus character — that is the goal of true education.’ – Martin Luther King, Jr.

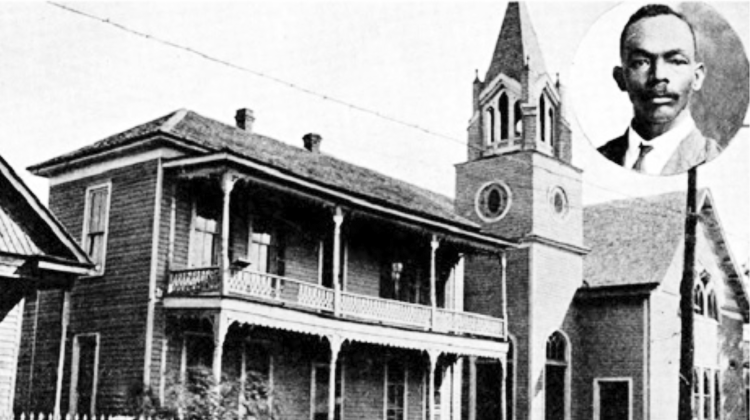

Minister and educator Woodson Pipkin, a pioneer in the field of education, is among Beaumont’s most distinguished citizens. He was also the first Black preacher and the first Black schoolteacher in Beaumont, according to local historical accounts spread throughout the Lone Star State.

According to the Pipkin biography housed at Stephen F. Austin University, Lamar University adjunct history instructor and McFaddin-Ward House Museum Interpretation and Education Curator Judith Linsley detailed the life of a man who, despite being born into slavery, battled to secure his own education – and the education of others denied access.

According to the history of St. Paul AME Church, Pipkin arrived in Beaumont with his enslaver, the Rev. John. F. Pipkin, Beaumont’s first permanent Methodist minister, when the area was still under pre-Civil Rights rules and regulations. Despite being in direct contradiction of southern laws, The Rev. Pipkin taught his namesake to read and write so that he, too, could understand and explain the gospel.

After emancipation, St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church was organized in 1868. It is one of the oldest churches in Beaumont and today’s congregation worships in a brick sanctuary at 3320 Waverly St. The church celebrated 150 years or worship in 2018.

According to Linsley, on Sundays, the church doubled as a house of worship, as well as a schoolhouse where many adults were able to learn how to read and write.

As reported in the months and years following emancipation, southern Black churches not only served as the religious center of Black communities, but also as the bustling centers for education, social and political endeavors.

In 1870, Pipkin and Charles “Pole” Charlton established a school for Black students near the Jefferson County Courthouse. They had two students the first term, but enrollment soon increased. Later, the school was moved to the second floor of Pipkin’s home; then, about 1873, to a structure on Bowie Street. By 1878, Pipkin and Charlton had started another school in the Live Oak Baptist Church, which was later moved to the corner of Neches and Wall streets.

Besides teaching and preaching, Pipkin earned money however he could – and was proficient in many trades. At one time, Pipkin manned a team of horses and mules to perform “heavy work.” One of his first jobs was working for William McFaddin, clearing fallen trees along the road from downtown Beaumont to Collier’s Ferry (a long stretch of several miles along the riverbank). Pipkin earned $100 for the task.

Years later, Pipkin operated a profitable drayage (hauling) service, delivering merchandise that came in on the trains from the freight depots to local department stores, such as Nathan’s and the White House.

During his life, Pipkin accumulated an appreciable amount of property in downtown Beaumont, on the bank of the Neches River, including a two-story house. He also accumulated a number of children, including four daughters – Eva, Ida, Rebecca, and Ada.

Eva married Jacob Boyer and taught in a one-room schoolhouse in the town of Sabine. Ada married Louis Williams, who helped to build the jetties at Sabine Pass and was foreman of a lumber-loading crew at Sabine Pass. In 1915, a hurricane destroyed the Williams’ house and the couple moved to Beaumont, where Louis became a dock crew foreman at the Port of Beaumont.

The Beaumont School District, formed in 1883 for both Black and white schools within the city limits, dedicated one of the early African American elementary schools in the old north end to Pipkin, who knew that, with emancipation, came a vital need for education for the African-American community. Pipkin did something about it.

After a long life of advancing the educational opportunities of minorities in Beaumont, Pipkin died in 1918 and was interred at the Martha Mack Cemetery, which was named for a 19th century African-American Beaumont resident. The cemetery is adjacent to Magnolia Cemetery on Pine Street.